by Simon Borg-Olivier and Bianca Machliss

Knee problems are amongst the most common physical problems experienced by adults in our western society – many students of yoga, arrive at yoga with a pre-existing knee problem, and some, unfortunately, get knee problems as a result of incorrect yoga practice.

Knee problems that occur as a result of yoga are often due to Western yoga practitioners who start yoga late in life with stiff hips and ankles trying to prematurely force themselves into extreme postures of the knee [such as those shown in Figure 1].

Hip stiffness is less common in non-Western cultures partly because of a lifestyle, which includes squatting to go to the toilet and sitting cross-legged since childhood.

About 20 years ago, after already teaching yoga for 10 years, our understanding of how to deal with knee problems was greatly improved when we both went back to Sydney University as mature age students to become physiotherapists. After many years of experimentation and research we successfully blended our understanding of traditional hatha yoga with western medical science to develop our synergy-style of yoga.

Synergy style is essentially a dynamic and meditative yoga, which applies the basic principles of anatomy and physiology of yoga to the western body.

Main problems of the knee

There are many types of knee problems – the most common ones seen by yoga teachers are likely to be:

- Torn knee ligaments

- Damaged knee cartilage (meniscus)

- Patella mal-tracking

- Hyperextended knees

There is not one specific yoga-based cure for all knee problems. However, intelligently applied exercise-based physiotherapy, which is based on the techniques of traditional hatha yoga, can be of assistance in most cases in managing and improving problems with the knee.

The three basic principles that should be adhered to when treating knee problems through yoga are:

- Do not do any exercise that causes or exacerbates any pain or problem.

- In order to treat the knee, it is good to also work with the hip and ankles as well.

- Train strength and flexibility simultaneously throughout the full available range of motion of a joint.

The knee joint complex

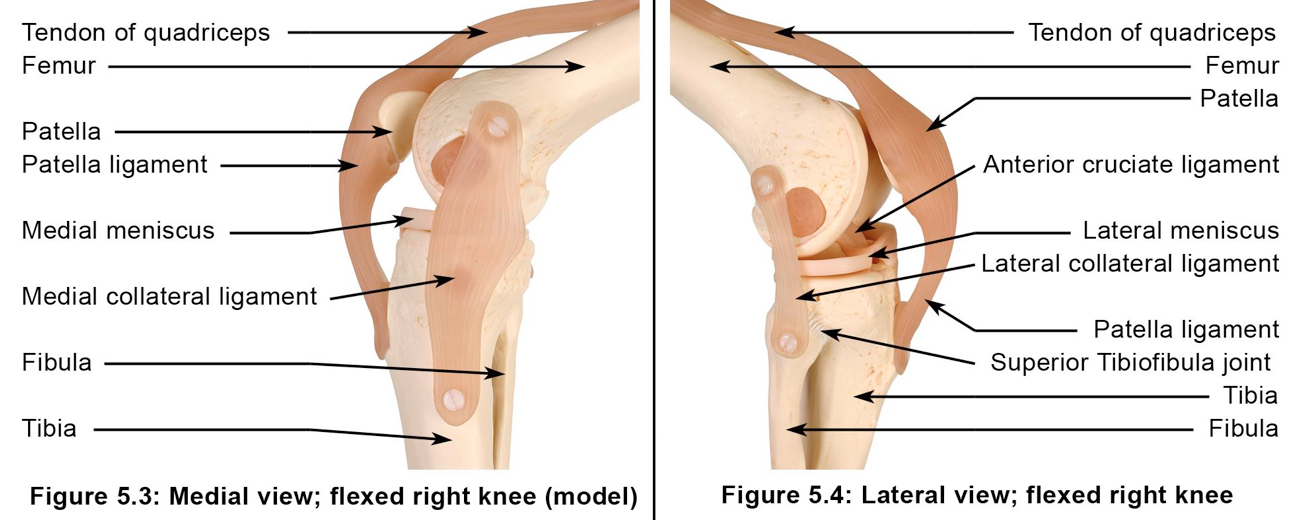

The knee joint complex [Figure 2] is not considered in anatomical terms to have a very good bony fit – it is basically the thigh bone (femur) sitting on top of the shin bone (tibia) held together with ligaments (anterior and posterior cruciate, medial and lateral collateral ligaments) and the surrounding muscles. The cartilage (meniscus) between the two bones helps increase the bony fit of the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia). The knee cap (patella) functions to protect the knee joint and increase the power of the front thigh muscles (quadriceps) by increasing the leverage of these muscles. As a result of the knee joint not being intrinsically stable it is important for the muscles surrounding the knee to be strong throughout the full range of functional positions.

Increase flexibility of the hips and ankles

Most problems of the knee are best addressed through strengthening not stretching the muscles around the knee. Being able to control the muscles around the knee is as important as developing strength in these muscles, i.e. being able to tense and relax the muscles in various knee, hip and ankle positions at will. In terms of flexibility, knee health is generally maintained and enhanced for yoga practitioners if the hip joint and to some extent the ankle joints are made more flexible.

Increase strength and control of muscles around the knee

A healthy knee needs to be stable and also has to have adequate blood flow. To keep the knee stable and to enhance the flow of blood, it is important to be able to co-activate (simultaneously tense) the muscles around the knee. Co-activation of knee muscles has been shown to be of assistance in the recovery of many knee problems [Aagaard et al., 2000].

It is well known that an important aspect of the treatment of most low-back pain is co-activation of the muscles around the lower trunk, in particular the lower abdominal muscles and the lower back muscles. Lower trunk muscle co-activation is essentially the mula bandha that is referred to in the Hatha-pradipika [Gharote &Devnath, 2001] and other old texts on hatha yoga. In ‘Light on Yoga’ [Iyengar, 1966] Sri B.K.S. Iyengar states ‘the three main bandhas (internal locks) are mula, uddiyana and jalandhara’.

Iyengar’s use of the word ‘main’ in this sentence implies that are in fact more than three bandhas. By comparing and contrasting bandhas such as mula and jalandhara it can easily be shown that the physical aspect of a bandha is essentially the simultaneous tensing (co-activation) of opposing (antagonistic) muscles around a joint complex. For example mula bandha (the root lock) involves the simultaneous tensing of opposing muscles (abdominal muscles and back muscles) of the lower trunk (lumbar spine joint complex).

Using this definition it is easy to see that bandhas can be and are often generated throughout the body to stabilise the major joints while regulating circulation. Janu bandha (the knee lock) involves the simultaneous tensing of muscles around the knee joint complex [Applied Anatomy and Physiology of Yoga’, Borg-Olivier and Machliss, 2005].

Most exercise programs for the knee should incorporate some form of janu bandha. If appropriately applied janu bandha can help to reduce pain and swelling around the knee, increase knee stability and help to improve the knee’s ability to move freely through a full range of joint motion.

Take a holistic (yogic) approach to knee problems – treat the whole body

As with treatment of any physical problem the whole person must be considered. Knee problems are often associated with other problems throughout the body, which include hip joint stiffness, ankle joint stiffness, weak lower limb muscles and loss of natural spinal curvature. Thus an overall body stretching and strengthening program such as intelligently taught yoga, is recommended to address all the associated problems of an unhealthy knee. In the beginning, the main aim in taking a person through the program is not to aggravate the existing condition. Then slowly, as their whole body responds to exercise the main problem itself can be addressed. The main problem can be made worse by an exercise program, which is not well thought out or not well applied, including yoga that is taught badly. An incorrect exercise program or incorrect treatment can exacerbate all the problems mentioned above. Simple general rules to adhere to when practicing yoga with knee problems are:

- Do not do anything that causes knee pain begin or to increase

- If the knee hurts when it is fully straight then bend it slightly

- If the knee hurts when it is bent then straighten it

In summary in yoga it is not generally sensible to adopt the ‘no pain –no gain’ mentality with knee problems and it is sensible to modify postures by either bending or straightening the knee, and/or activating (tensing) or relaxing the muscles around the knee to reduce knee pain.

Correct knee alignment

Correct alignment is an important issue for the correct flow of energy and also for the safety of the knee joint complex. The thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia) must generally be kept in line without too much, unprepared for, knee rotation of the shin bone (tibia) on the thigh bone (femur). For example in postures such as utthita trikonasana (triangle posture) [Figure 3] it is important to ensure that in the lower limb on which you are bearing most weight (the right side in Figure 3), the leg (below knee) is not turning out (externally rotating) while the thigh (above knee) is still turned in (internally rotating). Such a situation can damage the knee and can also compress that side of the lower back. This is often the situation that arises if the pelvis of the rear limb (the left leg in Figure 3) is lifted to high and/or inappropriately externally rotated (the rear thigh in all the standing postures, including Trikonasana, should be trying to turn inwards as described in a previous blog.

Vertical alignment is especially important for the beginner in postures like utthita virabhadrasana, utthita parsvakonasana [Figure 4] and other lunge-like standing poses. The beginner should not let the knee bend more than 90o and not beyond the heel in order to minimise stress around the knee-cap (patellofemoral joint). It has been shown that bending the knee greater than 90 whilst weight bearing puts up to seven times more stress on the knee. However it is interesting to note that Sri Krishnamacharya would often bend his knee beyond 90o in many postures, but because he was able to do this safely it was potentially making his knee more strong.

Similarly, Matthias St John (see the video above) is often seen to be in postures that would snap most peoples knees (Figure 3b) but because he trained to do this as an elite athlete he is safely able to do this and it actually made his knees stronger. So when he damaged his knee in an accident some time ago he came to see us and we were able to give him knee therapy that was at an extremely high level, with very challenging exercises that was actually able to do better than most people could do with an uninjured knee.

Move actively into knee postures

The safest way to take a knee into a posture is using the muscles of the hip knee and ankle and only using the arms as little as possible or preferably not at all. This active movement approach gives an added strength to the knee where it is needed to support ligaments and also causes reciprocal relaxation of muscles that do not help the movement. Even in relatively simple postures such as janu sirsasana [Figure 5] it is prudent to actively draw the bent knee into its final position using the muscles of that limb and if possible not assisting with the hands. Similarly it is therefore a good practice to learn to come into postures like padmasana (lotus pose) [Figure 6] in inversions such as headstand where it unlikely you can use your hands.

Modify postures to reduce knee pain

If the ability to straighten (extend) or bend (flex) the knee is limited due to pain or an immobilising injury then one should perform yoga postures only in the range of motion of the knee joint which is pain free and modify poses accordingly. For example postures such as janu sirsasana [Figure 6] should be practiced with the bent (flexed) knee straightened. Note that it is best for symmetry of the hips and spine to practice both sides of a modified posture in the same way.

Addressing knee problems in yoga

- Torn knee ligaments

Knee ligaments join bone to bone. It is common for knee ligaments and cartilages (see below) to be damaged by yoga practitioners who try to manipulate their knees into positions without having sufficient hip flexibility or knee muscle control for support. Torn knee ligaments can lead to pain, instability, swelling and loss joint movement in the knee. Many new yoga enthusiasts with a desire to achieve postures that require large amounts of flexibility in hip internal (inward) rotation, such as supta virasana (reclining hero pose) [Figure 6a] and postures that require large amounts of flexibility in hip external (outward) rotation, such as padmasana (lotus pose) [Figure 6b], often easily overstrain and/or tear knee joint ligaments and damage their menisci if they approach their practice incorrectly.

The most commonly ruptured knee ligaments are the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which joins the back of the thigh bone with the front of the shin bone, and the medial collateral ligament (MCL), which joins the inside of the thigh bone with the inside of the shin bone [Figure 2]. Rupture of the ACL and/or MCL usually results in a very unstable knee. The hamstring muscles act synergistically to the ACL (i.e. both the hamstrings and the ACL can perform the same function of stabilising the knee joint by preventing the shin bone moving in front of the thigh bone). Therefore, in cases of ACL tear/rupture/over-stretching, strength and control of the hamstrings is very important for aiding recovery and preventing further damage. Hip adductors (inner thigh muscles) are synergistic to the MCL. Therefore, strength and control of the inner thigh muscles is very important in cases of MCL damage. Tears of the MCL can heal depending on the severity of the tear, while ACL tears usually do not heal and require surgical reconstruction. All yoga poses that assist in the generation of janu bandha (the knee lock) will help stabilise the knee when knee ligaments have been damaged.

- Damaged cartilage (meniscus)

Knee cartilages (menisci) act as stabilisers, lubricators and shock absorbers inside the knee [Figure 2]. Damaged cartilage (meniscus) may result in instability, swelling and often pain and or locking of the knee joint in certain positions. Damage to the medial meniscus (inner knee cartilage) often happens at the same time as tears of the ACL and MCL, but can also occur independently to ligament tears. Damage to the medial meniscus is more common than damage to the lateral meniscus (outer knee cartilage), which often happens at the same time as of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL). If left untreated, meniscal tears may lead to degenerative changes and arthritis of the knee in later life. The menisci have a good blood supply in children, but only have a blood supply on their periphery from age 10 to adult. If torn, the periphery may heal but the central portion is unlikely to heal in adults. If locking, pain or instability persists, surgical intervention is often recommended via arthroscopy to clean the tear up so that it is no longer catching or causing pain and long-term inflammation in the knee. Only the outer third of each meniscus has a nerve supply therefore any pain felt from a meniscal tear must be from a peripheral portion of that meniscus. When practicing yoga with a meniscal tear do not repeatedly do movements that cause the knee to increase pain or make a clicking sound as this will usually cause the problem to worsen. A general principle is to simultaneously tense (co-activate) the muscles around the knee (janu bandha) before moving into or out of any posture and maintain a gentle grip of these muscles throughout ones practice and in every day life.

- Patella Mal-tracking

When the knee cap (patella) does not track correctly (i.e. slide over its correct path of movement) over the thigh bone (femur) this is referred to as patella mal-tracking. This painful problem, which can lead to instability and pain, can be due to imbalances in strength between a muscle on the inner knee called vastus medialis obliquus (VMO), which is usually weak, and a muscle on the outer knee called vastus lateralis. The VMO originates on the inner thigh muscle called adductor magnus. This is the anatomical basis for recommending inner thigh muscle (hip adductor) strengthening in cases of patella mal-tracking. Strength and flexibility training for the outer thigh muscles (hip abductors) such as gluteus medius is also recommended as this helps to stabilise the hips and increase their range of joint motion.

- Hyperextended knees

Hyperextended knees – where the back of the knee curves outwards like a banana – may be due to hereditary ligament laxity or because of over-stretching. It may be painful and have a deleterious effect on the entire posture of the person – often resulting in lower back pain. Do not hyperextend (over-straighten) the knee especially in weight-bearing postures. In cases of knee hyperextension, all postures that are weight-bearing on straight legs such as parsvottanasana [Figure 8] are best practised with the knee of a weight-bearing leg kept slightly bent (flexed), so the knee locking mechanism cannot operate and force the knees into hyperextension.

How to address these problems in yoga

What follows is a general approach to managing or treating most knee problems with synergy-style yoga. When this program is correctly applied it can help to relieve most people’s knee pain. These exercises and recommendations should nevertheless be used with caution and should be suitably modified for each individual so as not exacerbate their problems. Pain is a relatively good indicator of how an exercise program is progressing. Although some pain may not be a problem, beginners and untrained practitioners of yoga should avoid moving so deeply into a posture such that is causes their pain to be elicited or causes an increase in their resting pain. Also pain should not be increased directly after the practice. It is okay for a small amount of muscle tenderness to be present on the day following a strong exercise session but when beginning an exercise program for knee pain it is prudent to make the program quite gentle and then see how the body responds to that first. Over time and with consistent practice the intensity of the program can be gradually increased.

This synergy-style yoga programme is designed for people with non-serious knee pain. It may not be suitable for people whose pain is easily inflamed after any exercise. The program is not designed for practice during pregnancy.

Muscles that need to be lengthened (stretched) to improve the health of the knees

Assuming that the knee is flexible enough to fully bend (flex) and straighten (extend) the main stretching exercise should focus on stretching out stiff structures of hips, knees and ankles especially:

- Outer thigh muscles (hip abductors)

- Inner thigh muscles (hip adductors)

- Hip rotator muscles

- Rear thigh muscles (hamstrings / knee flexors/ hip extensors)

- Rear calf muscles (knee flexors / ankle plantarflexors)

Muscles that need to be strengthened to improve the health of the knees

There are five groups of muscles that are important to strengthen around the knee. These muscles groups [Figure 9] and how to activate them individually in many yoga poses are as follows:

- Front thigh muscles (quadriceps / knee extensors), which may be activated by ‘pulling up knee cap’ when the leg is straight.

- Inner thigh muscles (hip adductors), which may be activated by squeezing the thighs together from the heels.

- Rear thigh muscles (hamstrings / knee flexors/ hip extensors), which can often be activated by trying to pull the heel towards the buttocks, and/or by ‘pulling up the knee cap’ and simultaneously trying to bend the knee

- Rear calf muscles (knee flexors / ankle plantarflexors) can be activated by raising the heels off the floor or simply pressing onto the front of the foot

- Outer calf muscles (ankle evertors) can be activated by lifting the outer foot towards the ankle.

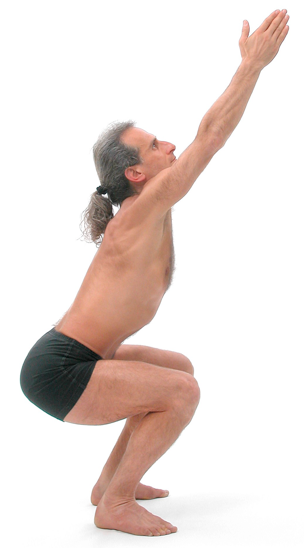

However in terms of knee health it is generally more effective to simultaneously tense (co-activate) these opposing muscles groups to generate janu bandha. For example it is possible to activate the quadriceps by first ‘pulling the knee cap up’ to activate the front thigh muscles, then — keeping the knee-cap pulled up — trying to bend the knee slightly using the rear thigh muscles (hamstrings) to utkatasana (powerful chair pose) [Figure 10]. This co-activation (janu bandha) is usually easier to activate if you squeeze your thighs inwards to activate the inner thigh muscles at the same time.

Two simple yet powerful one-legged exercises that can simultaneously tense the muscles around the knee and generate janu bandha are utthita pavanmuktasana (standing wind-releasing pose) [Figure 11] and niralamba virabhadrasana (unsupported warrior pose) [Figure 12]. Both of these poses generate janu bandha and give strength and stability specifically to the knee of the standing leg in utthita pavanmuktasana and the knee of the leg that’s in the air for niralamba virabhadrasana.

Please note that although it is possible to treat torn ligaments and damaged meniscus with yoga, if the injury is recent, it is advisable to consult an orthopaedic surgeon and physiotherapist regarding reconstruction of ligaments or trimming of meniscus surgically, as this can both increase stability and restore a person to normal activities of daily living. Yoga teachers are generally not qualified to make this decision for a student. Yoga can help to restore the knee to full health post-operatively provided it is done with care using the principles outlined above, and in conjunction with post-operative physiotherapy outlined by the surgeon. Most importantly during a yoga practice or class, it is the responsibility of the student and teacher to be sensitive to the capabilities of the body in any given moment, and not allow the ego to take over, which may result in an unnecessary knee injury.

FURTHER STUDIES IN YOGA AND YOGA THERAPY:

- You can learn more about yoga and yoga therapy by attending online courses: Yoga Therapy and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.

- Watch a FREE Workshop with Simon on Yoga Therapy

- You can also join our award winning online courses ‘Applied Anatomy and Physiology of Yoga’ (https://yogasynergy.com/shop/anatomy-physiology-yoga-online-course/) and ‘Advanced Yoga Fundamentals: the Essentials of Teaching Yoga (https://yogasynergy.com/shop/advanced-yoga-fundamentals-online-course/).

- Try our Online Yoga Teacher Training FREE for 7 days

This material for this blog is based on an article published the brilliant Australian Yoga Life Magazine some years ago and was subsequently translated into several languages, including Russian.

Share this Post

Comments 2

Great article Simon/Bianca-

Did either of you have surgery for the menisci injuries?

I had 50% of my medial meniscus removed around 12 months ago. Practice is back to where it was before the injury- but would be curious to hear of long term affect on the joint/practice if it is something you have experienced personally…

thanks!

hi Phil

No both of us did not have surgery.

both of us have pretty good knees still

Good yoga can be amazing

cheers and best wishes

simon